The most famous Jack Benny cartoon made at Warner Bros. is a bit of a disappointment.

Celebrity spoofs and references provided story and gag material for cartoons soon after sound became popular. Sometimes, ersatz versions of Hollywood and radio stars made up whole cartoons. Jack Benny began his regular radio show in May 1932, eventually playing a phoney version of himself. Cartoons from a number of studios soon began taking advantage of Benny and his characteristics. Let’s focus on Warners (including the Leon Schlesinger studio).

In

Into Your Dance (1935), Captain Benny emcees an amateur show on a boat, while in

I Love to Singa (1936), the host of a radio amateur show is Jack Bunny. Benny never hosted an amateur show, though he did play a showboat emcee in the 1935 film

Transatlantic Merry-Go-Round. Neither of the cartoon characters mentioned sound or look like him, but the Bunny in

Singa smokes a cigar just like Jack Benny.

The Woods Are Full of Cuckoos (1937) is a parody on the

Community Sing radio show starring Milton Berle but features other radio stars of the day turned into animals. Included once again is Jack Bunny, though this time an attempt is made to make him sound like Benny. And it’s not a very good one by Tedd Pierce, a writer who did voice work at the studio for a while. Mary Livingstone and Andy Bovine also appear; cowboy actor Andy Devine appeared with Benny off and on for several years. Livingstone may be voiced by Sara Berner, who later had a semi-regular role on the Benny radio show; Bovine is likely impressionist Danny Webb. They perform a one-gag play based on a film; the second half of the Benny show in the ‘30s generally consisted of a parody of a movie.

A radio host named Jack Lescoulie, later one of the originals on the

Today show on NBC, used to do a Benny impersonation on his show on KFWB called

The Grouch Club. Lescoulie was hired to provide the impression in several Warners cartoons. One was

Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur (1939), which features a caveman that doesn’t look like Benny and is identified with him only through the voice, his attitude to some extent, and his show-ending farewell line.

But there were other cartoons which had a more direct connection.

Meet John Doughboy (1941) includes a gag about “the latest war weapon: a land destroyer, 100 times faster and more effective than a tank.” When it skids to a stops, it turns out to be Jack Benny’s Maxwell containing caricatures of Benny and his butler Rochester, no doubt designed by assistant animator Ben Shenkman, who specialised in celebrity caricatures. The gag here would be obvious to any radio listener—Benny’s car was the slowest thing on Earth. Benny removes the cigar from his mouth and turns to the camera. “Hello again, folks,” he says (Lescoulie is voicing him), a play on Benny’s “Jell-O again,” greeting on the radio show (which changed to “Hello, again” when he began plugging Grape Nuts Flakes in 1942). Rochester is voiced by Mel Blanc and the scene ends with Carl Stalling playing the five-note Jell-O signature from the Benny show. Neither star is mentioned by name. Both the scene and

Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur end with the ersatz Benny aping the real radio Benny and saying “Good night, folks.”

Lescoulie-as-Benny can also be heard in

Slap Happy Pappy (1940), again as a cigar-smoking rabbit named Jack Bunny, greeting the audience watching the cartoon with “Hello again, folks.” Bunny is about to bash a black Easter egg to bits when a Rochester chick (Blanc) pops out. And there’s a Devine sound-alike chicken (Webb) We get another cigar-smoking Jack Bunny rabbit “Hello Again”ing courtesy of Lescoulie in

Goofy Groceries (1941). In this one, the cartoon ends with a stick of dynamite exploding, turning Bunny into Rochester (Blanc), who finishes the short spouting a reference to the “tattle tale gray” ad slogan of Fels-Naptha Soap (not a Benny sponsor, but director Bob Clampett loved radio references in his cartoons).

Benny makes a cameo appearance in

Hollywood Daffy (1946). He’s at a claw machine digging out an Oscar, which gets dropped when a security guard runs into him while chasing Daffy. Blanc plays Benny. The routine reflects a running gag for several seasons on the Benny show where Jack was peeved that he had never been nominated for an Academy Award.

But the studio’s best attempt to parody parts of the Benny show probably came in

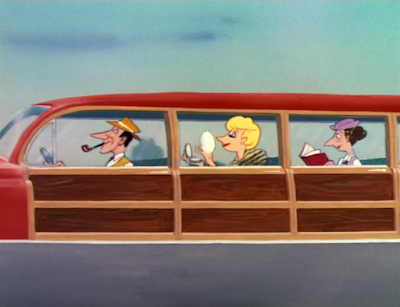

Malibu Beach Party (1940). This short once again features Shenkman’s celebrity caricatures but the story by Jack Miller centres around Benny, who is again named Jack Bunny even though he’s a human and not a rabbit. Bunny’s smoking a cigar and the cartoon opens with him being cut down to size by Mary Livingstone (Berner). There’s a strolling Andy Devine (Webb) shouting “Hi-ya, Buck!” just like on the radio show, a bandleader named Pill Harris (Lescoulie again), tanned, smiling and curly-haired like Benny’s orchestra front man Phil Harris, and an appearance by “Winchester” (Blanc), who engages in Rochester-like banter and typical Benny show jokes like filling drink glasses with an eye-dropper. The cartoon ends with Bunny forcing Winchester to listen to his mediocre violin playing (by sitting on him), a variation of a gag lifted right from the Benny show. Stalling again adds the Jell-O signature to the score. Why Benny’s name kept being parodied while Mary’s wasn’t is a mystery that we will likely never solve.

This brings us to the cartoon we referred to at the top of the post, and we have to jump ahead a few years to the age of network television. Bob McKimson was now directing at Warners and his storyman Tedd Pierce got the idea of satirising “The Honeymooners” by turning all the characters into mice and calling it

The Honey-Mousers. This 1955 release basically took all the catchphrases from the Gleason show and had Daws Butler and June Foray provide voices reminiscent of three of the comedy’s four characters. That was about as far as the satire went. There was no attempt to send up any of plots you’d find in a “Honeymooners” episode, nor Gleason’s bug-eyed takes (which would have worked well in animation); it was a garden-variety mice-versus-cat cartoon.

The cartoon must have been popular as another one with the characters followed the next year. And it seems to have inspired what was called a “switch” in vaudeville—take the same idea and give it a different spin.

McKimson told historian Mike Barrier that Benny wanted the Honey-Mouser treatment. So Pierce turned the cast of the Jack Benny show into mice and wrote

The Mouse That Jack Built.

There was a difference, though. In this cartoon, members of the Benny cast agreed to provide their own voices, including Jack Benny himself. Convincing them likely wasn’t difficult. Mel Blanc was a personal friend of Benny. McKimson lived on the same street as Benny, Roxbury Drive in Beverly Hills. And Pierce had a bit of a connection, too. He drank at Brittingham’s, the restaurant/bar in Columbia Square on Sunset Boulevard adjacent to where Benny had made his CBS radio shows (the Benny TV broadcasts came from Television City on Fairfax).

Pierce had a golden opportunity to do a

Malibu Beach Party-type send up of the Benny show; whoever designed the characters did an excellent job so they looked like mouse versions of the cast. Unfortunately, Pierce didn’t do an awful lot original with the concept and likely didn’t get any help from McKimson. He seems to have settled for the caricature itself being the gag and that wears thin rather quickly.

There are little bits of parody that shine through and the cartoon starts off well. Composer Milt Franklyn opens the short by incorporating the Kreutzer Etude No 2 into his sub-main title theme, the same music that Benny butchered on his radio show when receiving violin lessons from Professor Le Blanc (played by Mel Blanc). After the titles, there’s a shot of a stylised version of Benny’s real house on Roxbury Drive and a sign that’s a takeoff on Benny’s claim of being “star of stage, screen and radio.” A mini-sign is attached reading “Also Cartoons.” Cut to a Benny-like mouse who is given the bent wrists and flouncing walk Benny was famous for on television. But Pierce proves to be no George Balzer or Milt Josefsberg when it comes to writing for Benny, at least when he’s not using their material. The Rochester mouse makes a crack about Benny’s baby blue eyes. The best Pierce can muster is “They are nice, aren’t they?” And the sing-song question and answer between Benny and Rochester is far more sedate than what you’d hear on radio; McKimson needed to punch up their energy to compensate for not playing in front of an audience.

Fortunately when this cartoon was released in 1959, general audiences were familiar enough with Benny that they’d get the references. There’s a vault guarded by Ed, who is unseen to save money on animation (he is voiced by Blanc instead of Joe Kearns, who was the character most of the time on radio). There’s Rochester singing off-key. There’s the Maxwell. But all Pierce does is repeat radio/TV routines, treating them straight. The one nice bit of satire, my favourite moment in the cartoon, is when Don Wilson shows up to read the commercial. While he fits in the word “lucky” as in Lucky Strike cigarettes, Benny’s radio sponsor during his last decade or so, the spot appropriately refers to Warners cartoon characters:

If you’re feeling mighty lucky,

Bugs Bunny-ish and Daffy Ducky,

And tot you taw a puddy tat

There just one thing to do for that.

The plot also revolves around a cat that wants to eat the Benny mouse troupe, and appeals to Jack’s cheapness by inviting him to a free dinner at the Kit Kat Klub. Pierce fits in a wine pun where Jack exclaims that he likes “a good mouse-catel.” Jack and Mary stroll into the cat’s mouth, which slowly closes. Suddenly, Jack realises he’s been eaten (“Yipe!” he says in true Benny fashion) and yells for help.

Now, we get a nice twist. The cartoon fades out and in fades a live-action Benny, squirming in his chair and calling for help. Oh, he realises, it was all a dream. Or was it? We and Jack hear echoing violin music. Cut to a still photo of a real cat with the cartoon Jack and Mary escaping from a superimposed drawn mouth and running away and then through a mouse hole in the wall on the next shot. Cut again to the real Jack, turning to the camera with one of those expressions he became famous for on TV. Compare how he looks to how the Mouse Benny did it earlier in the cartoon.

The sight of Jack Benny in colour would have been fairly novel for many people in 1959. It loses its impact today.

The absence of Dennis Day hurt the cartoon a bit, but there may simply have not been enough time for him. Phil Harris, of course, left the show in 1952 to its detriment.

Anyway, the cartoon was a nice try for Warners but it should have striven for more than mere Benny duplication. When it did, the cartoon was very good.

The animators of this short were Tom Ray, Ted Bonnicksen, Warren Batchelder and George Grandpré, with layouts by Bob Gribbroek and backgrounds by Bob Singer, who is the only one in the crew still alive.

Incidentally, the short had one effect that lasts even today. It was viewed by a little girl named Laura Leff. She knew nothing of Jack Benny but liked the cartoon. So she started to learn about Jack Benny and set up a fan club. Today, the

International Jack Benny Fan Club has a fine newsletter and a friendly presence on the internet, especially

on Facebook.